Brasilia: May 25, 2020. Brazil is now the the world’s second worst-hit country in terms of coronavirus cases, behind only the United States. Not only is the rapid spread of COVID-19 overseen by a president who has openly denied the seriousness of the disease, Brazil is still recovering from an economic crisis and houses more than 13 million people in “Favelas” or slum areas where social distancing and hygiene routines are difficult to follow. Moreover, the lack of testing in the country is hiding the real numbers that are likely to be 15 times higher according to health experts.

As one of the coronavirus hotspots in the world, these factors and other vulnerabilities unique to Brazil makes it one of the most dangerous places for the rapid spread of the pandemic. A report by WHO collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease and Imperial College London the epidemic is not yet controlled in Brazil and will continue to grow.

Looming over political crisis

Since the virus began in the country, President Jair Bolsonaro has been grossly downplaying it by continuously thwarting international health protocols, encouraging protests in his country by defying social distancing and overall jeopardising a coordinated global response to fight the pandemic.

Looming over political crisis

Since the virus began in the country, President Jair Bolsonaro has been grossly downplaying it by continuously thwarting international health protocols, encouraging protests in his country by defying social distancing and overall jeopardising a coordinated global response to fight the pandemic.

Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro eats a hotdog in a street cafeteria, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Brasilia, Brazil.

Bolsonaro fired his health minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta over disagreements over the severity of quarantine measures to stop the spread of the virus in April. Just a month later, the new health minister Nelson Teich resigned from his position over the same reasons exposing the lack of coordination and chaos looming over the decision making process in the country.

Apart from this, the president has often been at odds with and opposed state governors and mayors who levied quarantine measures in their states from mid-March, touting them as economically harmful. He has openly encouraged lax quarantine measures and has himself participated in street rallies and social gatherings even when the numbers were climbing rapidly.

This lax quarantine rhetoric is profoundly affecting the implementation of successful social distancing. The number of people complying with social distancing in Sao Paulo, the most populous city in Brazil fell from about 70% on March 22 to just 47% on April 15. The fall in number ran parallel to the president’s rhetoric.

Demonstrators take a part in a protest in favor of Brazillian President Jair Bolsonaro in front of the Planalto Palace, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Brasilia. (Photo: Reuters)

Demonstrators take a part in a protest in favor of Brazillian President Jair Bolsonaro in front of the Planalto Palace, amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Brasilia. (Photo: Reuters)

This has also to do with the spread of misinformation regarding the virus, often by the president himself. Addressing reporters in Brasilia on March 26, Bolsonaro expressed confidence that Brazilians had already been affected by the virus and acquired antibodies to protect them, while acknowledging the greater risk the virus poses for the elderly population. Twitter suspended a few tweets by the president on the grounds of spreading misinformation regarding the pandemic and breaching the platform’s coronavirus regulations.

Social vulnerabilities in favelas and forests

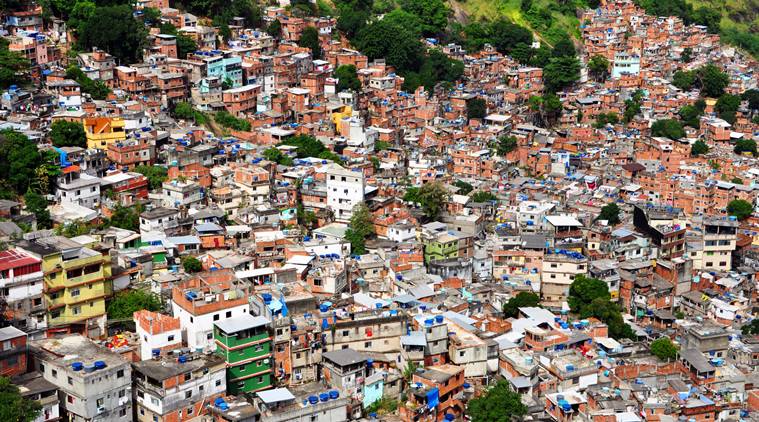

The swathes of over-crowded and densely populated slum areas or Favelas in Brazil where social distancing is harder to follow is making the country’s fight to overcome the coronavirus pandemic particularly difficult. Although coronavirus started spreading in urban areas it has rapidly penetrated into the favelas in the last two months.

These areas house over 11 million Brazilans and lack basic amenities like proper sanitation and access to clean water. According to Brazil’s National Water Agency, approximately 100 million people or almost half of the country’s population live without proper sewage systems. Bad sanitation conditions are potentially disastrous for the spread of coronavirus.

Although coronavirus started spreading in urban areas it has rapidly penetrated into the favelas in the last two months. (Photo: Creative Commons)

Although coronavirus started spreading in urban areas it has rapidly penetrated into the favelas in the last two months. (Photo: Creative Commons)

In most of these areas, people share a common toilet and hence cannot afford to follow stay at home orders. Even their daily water supply is procured from the outdoors creating additional spaces for spreading the disease. A survey conducted by Data Favela shows that 72% of favela residents in Brazil would run out of money in just a week of social isolation. Moreover, access to PPEs, face masks and other coverings is not widespread, even sanitisers are hard to procure.

According to the United Nations, the biggest challenge is that not all favelas have access to information regarding the basic guidelines of COVID-19 from the news or the internet. This makes it very difficult to instil the very alien hygiene routines — essential in combating COVID-19 — to be followed by the people staying here.

The lack of an integrated government response at the central level has forced several community activists, NGOs and local leadership to step in and take action. These organisations are distributing food, hygiene kits to vulnerable slum areas along with disseminating information regarding the spread of virus.

Physiotherapist from a group that specialises in providing mobile physiotherapy care, applies a Brazilian physiotherapy method called RTA (Re-Balancing Thoracic-Abdominal) while attending to a COVID-19 patient. (Photo: Reuters)

Physiotherapist from a group that specialises in providing mobile physiotherapy care, applies a Brazilian physiotherapy method called RTA (Re-Balancing Thoracic-Abdominal) while attending to a COVID-19 patient. (Photo: Reuters)

Brazil’s indigenous tribes are facing similar issues and form another highly vulnerable social group. Since the pandemic penetrated the isolated indigenous lands in the country’s Amazon region it has already claimed over 85 lives according to a tally by APIB, an organisation of the tribes. The actual count is believed to be much higher.

The indigenous people live far from urban healthcare facilities and find it difficult to inculcate the hygiene and social distancing norms required to fight the pandemic, much like the favela dwellers. Since the tribal population was instructed to stay in their own villages, acquisition of essential commodities have become a problem. Necessities like kerosene are in limited supply. Agents who enter their territories do not always wear protective equipment. The ongoing climate crisis and now the coronavirus crisis has seriously affected the livelihood of Brazilian tribes.

Hospitals maxed out

Brazil’s public health system, through which more than 70% of the country’s population receives services, is saturated as hospitals across the region face an influx of patients. Brazil’s former health minister had said the health system will start entering a state of collapse from the end of April.

Brazil’s relatively poorer regions (in the North) are facing an acute shortage of ventilators and other critical care facilities. State hospitals are operating at over capacity in many areas. In Rio de Janeiro, government hospitals are operating at over 85% of ICU capacity and the system is expected to collapse. Similarly, in Sao Paulo, ICU capacities are almost full.

The virus has started spreading at a time when Brazil already grapples with other diseases such as dengue that contribute significantly to hospital usage. (Photo: Reuters)

The virus has started spreading at a time when Brazil already grapples with other diseases such as dengue that contribute significantly to hospital usage. (Photo: Reuters)

According to data by Brazil’s Federal Council of Medicine (Conselho Federal de Medicina), there are 0.8 beds per 10,000 people in Brazil’s northeast region. Similarly, Brazil’s national average of available ICU beds is 1 per 10,000. The worst affected regions the North, Northeast and Centre-West are the poorest and most dependable on the public health system. These regions are also seeing a rapid growth of coronavirus infections.

The virus has started spreading at a time when Brazil already grapples with other diseases such as dengue that contribute significantly to hospital usage. The period January-May is the peak spread of dengue throughout the country resulting in higher rates of hospitalisations.

Economic projections

The coronavirus pandemic is affecting Brazil in an already struggling economic environment. The country’s economic minister, Paulo Guedes, said Brazil could face severe economic consequences like production seizing up and food shortages within a month’s time due to the pandemic.

A report by IMF’s World Economic Outlook (April 14 2020) said post the pandemic Brazil’s economy is expected to shrink by 5.3% and that it needs to start preparing for a serious depression. This could be followed by an unprecedented decline in trade and severe currency fluctuations. Brazil will face all these shortcomings at the backdrop of an already low annual growth of 2.2% from the year 2000 to 2015, as calculated by the World Bank.

In fact, the entire region of Latin America will see an average economic drop of 4.2%, this is expected to be more severe than the 2009 recession. Brazil suffered other major economic blows due to the pandemic. The fall in oil prices in late April affected the country as it is heavily dependent on oil revenues. For millions of Brazilians working in the informal sector, the lockdown measures have already been disastrous. All these factors are expected to be followed up by a massive jump in unemployment, poverty and inequality.