New Delhi 12 May 2020. In the wake of COVID-19, millions of school and college students all over the world are taking classes via Zoom. Such distance learning, however, is not merely for the young. It can be enormously helpful for us older folks too. Thus, earlier this week, I enrolled in a two-hour class conducted by the country’s top public health experts, which gave me a deeper and more profound understanding of the current pandemic than ‘prime-time’ TV shows ever could.

Of the panelists, two were civil servants who served many years in the health sector, two were doctors-turned-community health specialists, two others doctors-turned-university professors. These six experts have three things in common; all live and work in India, all are highly regarded by their professional peers, and none have been consulted by the Modi Government. (Among the modest hopes of this column is that the latter may yet be reversed).

I took copious notes as I listened to these experts, and summarize what I learnt in what follows. It now seems clear that while the initial lockdown controlled the spread of the disease, the government did not use the time and breathing space gained to vigorously promote testing, accurately identify potential or emerging hotspots, or convey accurate and reliable information to the public.

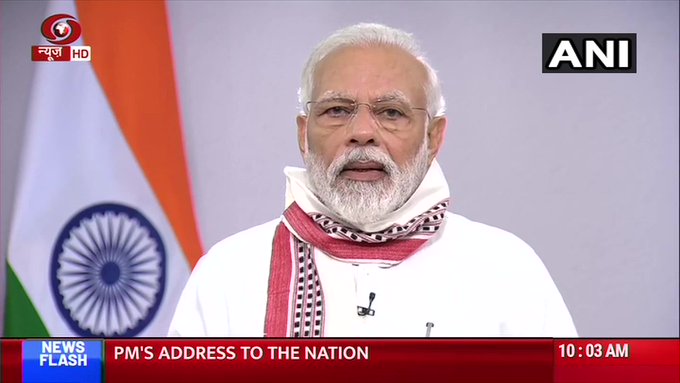

he social and economic aspects of the lockdown have been widely criticized. By its precipitate action, the central government abruptly deprived citizens of jobs and livelihoods. By giving them only four hours’ notice, millions of workers were stranded far away from their homes, with no food, shelter, or cash. Yet, even from the point of view of public health, the first lockdown was very poorly planned. In mid-March, few workers who wished to return to their villages were infected. If these citizens had been given time to travel home, they would have re-entered their villages in a safe manner. Six weeks later, when the government wants to belatedly make amends by arranging trains for migrants, tens of thousands of returnees are carriers of the deadly virus. The centre is now trying to pass the buck on to the states, but it is, of course, the Prime Minister who bears ultimate responsibility for what is unquestionably the greatest man-made tragedy in the country since Partition.

There has been a pronounced class bias in how the lockdown was conceived and executed. As a result, already pervasive social inequalities have deepened even further. The loss of jobs and incomes has pushed millions of working-class Indians into near-destitution. As they shall now have less food to eat, and of poorer quality too, they will become more vulnerable to diseases of different kinds, not just COVID-19.

There are many things the Modi Government has done wrong with regard to the pandemic. As the result of their mistakes, the devastation has been immense. Oureconomy is in the doldrums, our social fabric is strained, our health system over-stressed. Yet there are many things the Modi Government could still do right. In this regard, the experts I listened to offered five major pieces of advice.

First, there should be absolutely no sense of complacency. So far the virus has not spread very deeply into the countryside. States like Assam, Odisha and Chhattisgarh have a low incidence of cases. But this is likely to change in coming months, and as the cases in these states multiply, the fragility of their public health systems will be exposed.

Second, the government must get on board our top epidemiologists working outside the ICMR system. Experts who helped us effectively tackle HIV, the H1N1 virus, and polio in the recent past have not been consulted. Their knowledge could have been of immense value in framing suitable policies to tackle this latest epidemic. It still can.

Third, epidemics are not just a biomedical issue, but also a social issue. There are signs that COVID-19 has already led to a rise in alcoholism, domestic abuse, depression and suicide. These, as much as death and disease, poverty and unemployment, will be the inevitable consequences of the pandemic. Therefore, it is not just public health experts, not just economists, but sociologists and psychologists with domain expertise who must also be consulted by the government.

have done outstanding work in recent weeks.

As we look to the future, we can take hope in the fact that, as compared to Europe and North America, ours is a much younger population. In India, the pandemic may (with luck) claim fewer lives. That said, once it has passed, we will need to rebuild our economy, our society, and our health systems with the greatest care and attention. If this rebuilding is to happen, the ways of the union government must change dramatically. It must learn to give states greater autonomy (as well as more money). It must allow independent thought and civil society organizations to flourish, rather than seek to suppress them at every turn. But the ways of the Prime Minister must radically change too. He needs to listen more attentively, and consult more widely. He must never again rush unilaterally and without thought into decisions whose awful consequences he has not anticipated.

As the panel discussion I listened to so strikingly showed, the country has a vast array of scientific and administrative expertise that the Prime Minister and the union government can call upon for advice in coping with a post-COVID world. Whether they are large-hearted and open-minded enough to do so is, of course, another matter altogether.

(Ramachandra Guha is a historian based in Bengaluru. His books include ‘Environmentalism: A Global History’ and ‘Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World’.)